22 January, 2016 Here’s how you can engage with students and teachers without leaving them speechless. When he finished, the classroom was very still. The talk had stunned my students into silence. Finally, one asked, “Do you like your research?”

Here’s how you can engage with students and teachers without leaving them speechless. When he finished, the classroom was very still. The talk had stunned my students into silence. Finally, one asked, “Do you like your research?”

When I taught high school science, I was always eager to work with scientists in the community. My first guest speaker was a chemistry professor. We agreed he would talk some about his work and have a long question-and-answer period that might lead to an interesting discussion.

He spoke for nearly an hour on his work research in hypervalent molecular orbital theory. Even I found this painful.

The bell rang before he could answer. I remember him muttering how he thought it went well as be followed the students out the door. I was grateful that even my most rambunctious students had at least appeared attentive throughout the ordeal.

Learning to listen

Later that year, I meet with Profs. Scott Grayson and Hank Ashbaugh of Tulane University in New Orleans to discuss a collaboration. This time, I made sure we agreed outright that whatever we did would focus on the student experience. To do this, we had to listen to each other. So, with a series of planning meetings, we created a program that was integrated into my curriculum.

Hank and Scott brought students from a community service-oriented course to perform a series of demonstrations related to polymer science; then over a period of weeks, their students returned to teach short lessons on the topic. After each step, we reflected together on how the work was progressing and how it could be improved. Our intentionality was essential. The project consumed a surprising amount of energy, but it was well worth the effort to see my high school students learning from the university students. Hank and Scott’s students undoubtedly also learned some lessons of their own, as for some it was their first experience teaching.

Share your classroom tips

Scott initially contacted the chair of my school’s science department, finding her email address on the school’s website. This is one of many similar cold calls I received over the six years I taught in high school. I was always happy to discuss a collaboration, and most of the time, nothing developed. However, each time a scientist or engineer was eager to listen, we developed a successful student interaction. This resulted in three successful talks, each carefully planned to avoid my earlier mistakes. Several community members volunteered to mentor one of our afterschool programs. Two professionals from the community created internship opportunities for students. We also planned some excellent trips to visit university labs and field sites.

Spend time with students rather than program development

Without a doubt, the task of locating a school group to work with dissuades some prospective collaborators altogether. Cold calling, on my part as a teacher, or on the part of the research professional has produced some excellent results. However, there are many well established programs already organizing the major tasks. Many schools have teams that participate in nationally (or even internationally) organized competitions in science and engineering that coordinate volunteers, such as FIRST and Intel ISEF.

For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology (FIRST) is a leading international organization that sponsors robotics challenges and competitions for students from kindergarten through high school. In its flagship FIRST Robotics Competition, teams of high school students spend six weeks designing a robot to compete in a competitive team sport of other robots in regional, national and international invitationals. Unlike its younger sibling, FIRST LEGO, the full-blown Robotics Competition features 120-pound wirelessly controlled giants hurling yoga balls and wielding trash cans in manic competitions to challenge students’ abilities to engineer and strategize. As a former FIRST coach at the New Orleans Science and Math High School, our team depended on technical skills from volunteer graduate students and the time and patience of volunteer business professionals willing to coach the students through the interpersonal skills they need to be successful fundraisers and teammates. Through FIRST competitions, students experience the pleasure of completing a major cooperative project, become eligible for extensive scholarships, and add an attractive item to their resumes. More importantly, their interactions with adults with necessarily diverse skill sets support highly transferable skills that are useful throughout life.

The INTEL International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) bills itself as the world’s largest pre-college science competition, inviting over 1,700 students annually from local science competitions to participate in regional and national fairs. To mentor students at the local level, mentors need to do the legwork of contacting local high schools. On regional and national level, however, the ISEF is constantly seeking judges with technical expertise. In this way, scientists and other technical professionals can support young people conducting science, providing them with feedback and encouragement but without the structured time commitment required to mentor a team sport like robotics.

I highlight these two programs because their robust national volunteer support services websites make it easy for a prospective mentor to find opportunities. Another project of interest is the Million Women Mentors, a clearinghouse for mentorship opportunities that seek to close the gender gap of women entering STEM fields. All professionals, regardless of gender, are welcome to use the service in support of encouraging young women to pursue careers in STEM fields.

Many other worthy organizations exist that require more effort from volunteers to find opportunities. The Science Olympiad and the International Olympiads in Biology, Chemistry, Informatics, Linguistics, Math and Physicsencourage excellence through academic and engineering challenges. Volunteers can contact representatives from their home state or country or a list of participating schools. Websites of local schools also list programming of interest to science professionals, and some schools have volunteer and mentorship coordinators. In my state, the New York Academy of Sciences Afterschool STEM Mentoring program recruits graduate students and postdoctoral scholars from universities to volunteer to mentor underserved students one afternoon a week.

Some schools, such as the NET Charter School in New Orleans, which I co-founded, integrate community mentorship into the curriculum. These opportunities allow scientists and technical professionals to have a direct impact on individuals or small groups of students, which is often deeply meaningful for both students and mentors.

Mentoring teachers

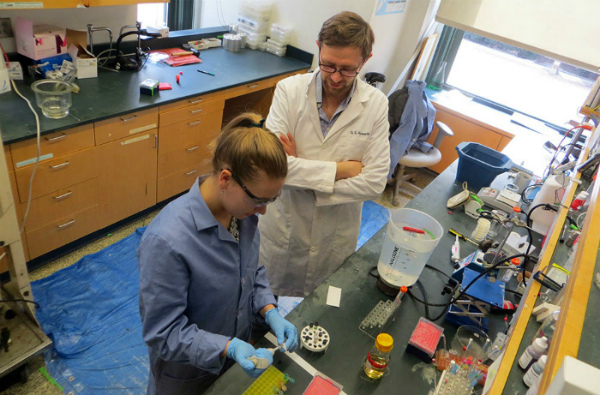

One way researchers can enhance classroom education is by supporting science teacher development. Inviting a science teacher to conduct research in your laboratory is one particularly powerful way to do this. Few science teachers have had the opportunity to conduct laboratory science, and it’s a pity considering that such experiences capture the essence of the skills science teachers are trying to impart. A rigorous research experience, completed either part time or over one or more summers, enhances content knowledge and laboratory techniques. Moreover, the process of actually collecting, interpreting and communicating data gives the science educator unparalleled insight into how to incorporate these skills into the classroom.

Before I taught high school, I had completed research projects in both university and industrial laboratories, so I felt I had a solid grasp on conducting research. Yet, when I undertook a project in enzyme kinetics with Prof. Larry Byers at Tulane University (an experience I found by talking with Scott and Hank) during the summer between school years, I felt inspired to change my classroom environment. I examined my research experience with the lens of a classroom teacher, and in doing so, I returned to my classroom the next year with far more emphasis on data collection and analysis, focusing more on the skills I had struggled with. I also introduced a kinetics unit, a concept I previously rejected as too advanced for the average high school student. Conducting research in the field actually allowed me to reevaluate how to communicate the concepts, despite the difficult nature of the topic, and the results were positive.

Many colleges and universities, and some corporations, have well established programs that coordinate research experiences for teachers and can even arrange stipends. These programs are typically seeking investigators willing to participate. As much as possible, the teacher should have an independent project that can be completed within the allotted period of the program. This provides a sense of ownership and accomplishment and allows the teacher to create a poster or other tangible outcome from the experience. The average science teacher is likely to be more organized than a new graduate student, but they still need mentorship from laboratory researchers in order to have a successful experience. Partnerships between advanced graduate students and teachers allow each to learn from the other.

Getting professional help

For those struggling to find a way to get involved, there are other resources that can help. All major professional scientific and technical organizations (e.g. ACS, APS, IEEE) have education and outreach offices with listings of potential opportunities, and helpful professionals happy to help you brainstorm. There are also dedicated science education organizations such the National Science Teachers Association in the US, and discipline-specific education organizations in biology, chemistry , engineering and physics have copious opportunities and staff members to assist in coordination.

Conclusion

Even though my first classroom speaker may have frightened students with molecular orbital theory, it wasn’t a complete loss. The day after the disastrous talk, my students did in fact have questions they had been too timid to pose directly. Mostly, they wanted clarification on what he actually did on a daily basis – and if it mostly consisted of boring high school audiences. One student asked the key question, “What were we supposed to learn?”

During my first year teaching, I was so harried and exhausted that I was happy if no one was injured by the end of the day. I hadn’t yet learned to focus on student outcomes. I treated my guest speaker like a break from planning. And based on his slideshow, he treated his visit like any other academic talk.

Enthusiasm and a little time are the only essential components to build a relationship with students and their teachers. Thoughtful planning and listening to stakeholders is required to make the relationship worthwhile and allow it to thrive.