April 06, 2017

Summarising your journal paper effectively helps to ensure that it reaches the right audience, say James Hartley and Guillaume Cabanac.An abstract is a crucial element of any journal article. It heads and summarises the text, and it can sometimes appear alone in separate lists of publications. So, what should you do to make yours as effective as possible?

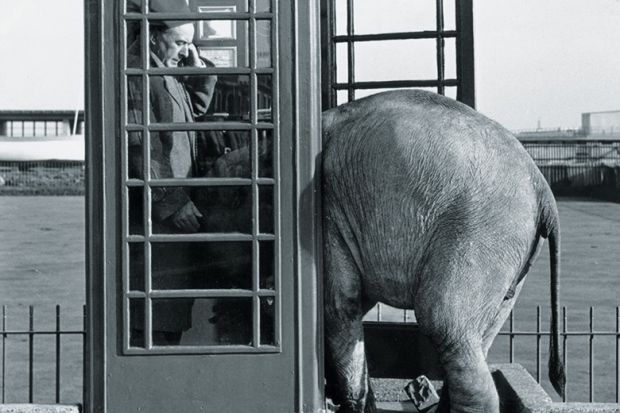

Source: Getty

Tight squeeze: ‘remember that the essential compression needed in an abstract may make it difficult for others to follow’

There are two standard forms of abstract: the “block format” abstract and the structured abstract. An example of a block format abstract for the article “Book reviews in time” that James Hartley and others published in Scientometrics in 2016 might read as follows (although it can help to include a few line breaks): “This paper focuses on the issue of whether or not academic writing changes over time. We examine a selection of book reviews written by five authors over 20-25 years. The data show little evidence of change for each of these authors as measured by readability scores and grammatical features. These findings are in line with earlier ones that suggest that academic writing styles are fixed fairly early on and do not alter much with time.”

A structured abstract might read thus: “Background: there has been little research examining how academic writing changes over time.

Aim: to see whether an author’s style, when writing an academic book review, changes over time.

Method: we examined a selection of book reviews written by five authors over 20 to 25 years. For each author, we recorded the number of words and paragraphs, the average sentence length, the use of passive tenses, and reading difficulty, as measured by the Flesch Reading Ease Readability Formula.

Results: the data show that while individual authors vary in their styles, each is consistent across the 20 to 25 years.

Conclusions: academic writing styles are fixed fairly early on and do not alter much with time.”

Research indicates that structured abstracts contain more information, are easier to read and perhaps recall, and are generally welcomed by readers, although it is best to follow the style of the particular journal. In either case, remember that the essential compression needed in an abstract may make it difficult for others to follow. Readability tests sometimes reveal that they are less readable than the body of the paper. Try to avoid this by ensuring that abstracts are not too technical and do not rely on specialist jargon.

There are a number of other things to bear in mind when producing abstracts. It is useful to include electronic links to previous research and a list of keywords to facilitate indexing and computer-based search (provided that you make the words precise enough). It is currently fashionable, especially in journals published by Elsevier, to give a few highlights of a paper (perhaps “Academic writing styles change little with age when writing book reviews” in the case of our sample article) either alongside the abstract or after the title on the contents page.

Another way of flagging up key messages is to incorporate a layperson’s abstract alongside a more technical one, or boxes answering questions such as “What is already known about this topic?”, “What does this study add?” and “What are the implications of this study for practice and/or policy?”

Some journals now require authors to produce a tweetable version of the abstract to facilitate rapid dissemination of the contents. Others ask for a graphical abstract to provide “a single, concise pictorial and visual summary”, as Elsevier puts it on its website, although it is often a challenge to present the findings in a way that readers can understand without reading the paper first. Yet another option is a video abstract incorporating brief interviews with the author(s).

To communicate effectively through all media, always keep in mind who the paper is for. If in doubt, check with appropriate readers, whether they be students, fellow authors or subject-matter experts.

James Hartley is emeritus professor of psychology at Keele University. Guillaume Cabanac is associate professor of computer science at the University of Toulouse.

Originally published at: